20s & 30s

FREE webinar – Improving Employment Outcomes

Presented by Joseph Ryan, Ph.D and the team from the Clemson LIFE program. This panel presentation by ClemsonLIFE (Learning is for Everyone) reviews evidence-based strategies for improving employment outcomes for individuals with ID, including training in assistive technology, community mobility, and employment soft skills.

The GLOBAL Medical Care Guidelines for Adults with Down Syndrome provide first-of-its-kind, evidence-based medical recommendations to support clinicians in their care of adults with Down syndrome. This life-changing resource as published in JAMA covers 9 topic areas deemed critically important for the health and well-being of adults with Down syndrome and outlines critical future research needs.

NDSC is proud to be a key supporter of GLOBAL’s work to bring these to clinicians and families. When you visit the GLOBAL webpage you can download the full guidelines, the guidelines toolkit (a great checklist to take to your appointments), and read more about the authors & workgroup.

Find the guidelines here

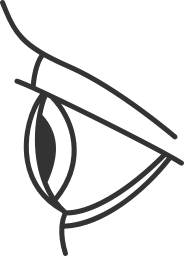

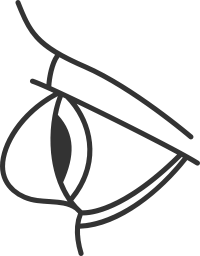

Eye problems and vision disorders are especially common in individuals with Down syndrome.

What is keratoconus?

Keratoconus, often referred to as “KC”, is an eye condition in which the cornea weakens and thins over time, causing the development of a cone-like bulge and optical irregularity of the cornea. Keratoconus can result in significant visual loss and may lead to corneal transplant in severe cases. Although somewhat rare in the general population, KC affects between 5–15% of people with Down syndrome and can impact their ability to function at their highest level.

For more on KC, visit Ages & Stages – Tweens & Teens

“Self-Talk” in Adults with Down Syndrome

By Dennis McGuire, Ph.D., Brian A. Chicoine, M.D., and Elaine Greenbaum, Ph.D, 2005.

Editor’s note: This article was originally printed in 1997 in Disability Solutions, Vol. 2, Issue 2, and excerpts are reprinted here with permission.

Do you talk to yourself? We all do it at different times and in various situations. At the Adult Down Syndrome Center of Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, we have heard repeatedly that adults with Down syndrome talk to themselves. Sometimes, the reports from parents and caregivers reflect deep concern that this behavior is “not normal” and symptomatic of severe psychological problems.

Preventing misinterpretation of self-talk as a sign of psychosis in adults with Down syndrome is a major motivation for this article. Too often, we believe, these conversations with self or imaginary companions have been equated with hearing of voices and treated with anti-psychotic medications (such as Haldol®, Mellaril®, or Risperdal®). Since it is extremely difficult to evaluate the thought processes of adults with cognitive impairments and limited verbal skills, we urge a very cautious approach in interpreting and treating what seems to be a common and at times very helpful coping behavior for adults with Down syndrome.

The Adult Down Syndrome Center was developed to address the health and psycho-social needs of adults with Down syndrome. Our records indicate that 81 percent of adults seen engage in conversations with themselves or imaginary companions.

Helpful self-talk

Families and caregivers should understand that self-talk is not only “normal” but also useful. Self-talk plays an essential role in the cognitive development of children. Self-talk helps children coordinate their actions and thoughts and seems to be an important tool for learning new skills and higher level thinking. Three-year-old Suzy says to herself: “This red piece goes in the round hole.” Then Suzy puts the red piece into the round hole of the puzzle.

We suspect that self-talk serves the same useful purpose of directing behavior for adults with Down syndrome. Consider the case of 22-year-old “Sam” (not his real name). His mother reported the following scene. She asks Sam to attend a family function on a Sunday afternoon. Sam’s regular routine is to go to the movies on Sunday afternoons. Sam tells his mother he will not go with the family. Then the mother asks Sam to think it over. Sam storms off to his room and slams the door. His mother overhears this dialogue:

“You should go with your family, Sam.”

“But I want to go to the movies.”

“Listen to your Mom!”

“But Sunday is my movie day.”

“You can go next Sunday”

Sam’s mother said he went to the family function with the proviso that he could go to the movies the next Sunday. Sam may have been talking to an imaginary person or arguing with himself, but Sam clearly managed to cope with a situation not to his liking.

In children without identified learning problems, the use of self-talk is progressively internalized with age. Moreover, children with higher intellectual abilities seem to internalize their self-talk earlier. As self-talk is transformed into higher-level thinking, it becomes abbreviated and the child begins to think rather than say the directions for his or her behavior. Thus, the intellectual and speech difficulties of adults with Down syndrome may contribute to the high prevalence of audible self-talk reported to us at the Center.

In general, the functions of self-talk among adults are not as well-researched or understood. Common experience suggests that adults continue to talk to themselves out loud when they are alone and confronting new or difficult tasks. Though the occurrence may be much less frequent, the uses of adults’ self-talk seem consistent with the findings about children. Adults talk to themselves to direct their behavior and learn new skills. Because adults are more sensitive to social context and may not want to overhear these private conversations, their self-talk is observed less frequently.

Adults with Down syndrome show some sensitivity about the private nature of their self-talk. Like Sam in the example above, parents and caregivers report that self-talk often occurs behind closed doors or in settings where the adults think they are alone. Having trouble judging what is supposed to be private and what is considered “socially appropriate” also may contribute to the high prevalence of easily observable self-talk among the patients visiting the Center.

In the general population, self-talk among older persons is frequently notable and, usually, easily accepted, just as it is with children. Among the elderly, social isolation and the increasing difficulty of most tasks of daily living may be important explanations for this greater frequency of self-talk. For adults with Down syndrome, these explanations also make sense. Adults with Down syndrome are at greater risk for social isolation and the challenges of daily living can be daunting.

Additionally, we have found that many adults with Down syndrome rely on self-talk to vent feelings such as sadness or frustration. They think out loud in order to process daily life events. This is because their speech or cognitive impairments inhibit communication. In fact, caregivers frequently note that the amount and intensity of the self-talk reflects the number and emotional intensity of the daily life events experienced by the individuals with Down syndrome.

For children, the elderly, and adults with Down syndrome, self-talk may be the only entertainment available when they are alone for long periods of time. For example, a mother reported that her daughter “Mary” spent hours in her room talking to her “fantasy friends” after they moved to a new neighborhood. Once Mary became more involved in social and work activities in her new neighborhood, she did not have the time or the need to talk to her imaginary friends as often.

Thus, the fact that adults with Down syndrome use self-talk to cope, to vent, and to entertain themselves should not be viewed as a medical problem or mental illness. Indeed, self-talk may be one of the few tools available to adults with Down syndrome for asserting control over their lives and improving their sense of well-being.

When to worry

The distinction between helpful and worrisome self-talk is not easy to cast in stone. In some cases, even very loud and threatening self-talk can be harmless. This use for self-talk by the adult with Down syndrome may not be that different from someone who rarely swears but screams out a four-letter word when hitting her thumb with a hammer. Such outbursts may simply be an immediate, almost reflexive outlet for some of life’s frustrations.

Our best advice about when to worry is to listen carefully for changes in the frequency and context of the self-talk. When self-talk becomes dominated by remarks of self-disparagement and self-devaluation, intervention may be warranted. For example, it may be quite harmless when “Jenny” yells, “I am a dummy,” once, right after her failure to bake a cake from scratch. However, if Jenny begins to tell herself over and over, “I am a dummy and can’t do anything right,” it may be time to worry and to do something.

A marked increase in the frequency and a change in tone of the self-talk also may signal a developing problem. For example, a caregiver reported that “Bob” had begun to talk to himself more frequently and not just in his room at the group home. Bob seemed to lose interest in his housemates and spent more time in these conversations with himself. Bob talked to himself, sometimes loudly and in a threatening manner, at the bus stop, at the workshop, and at the group home. Bob was diagnosed as experiencing a severe form of depression. Over an extended period of time, Bob began to respond to an anti-depressant and to his participation in a counseling group.

In another case, “Jim” (like Bob) showed a dramatic increase in self-talk. Jim refused to go to his workshop and to participate in the social activities that he once enjoyed. It turned out that Jim’s change in behavior was not due to depression. Instead, Jim’s family and staff at his workshop discovered that Jim was being intimidated and harassed by a new co-worker. With the removal of the bully from his workshop, Jim gradually regained his sense of trust in the safety of the workshop. His self-talk and interest in participating in activities returned to earlier levels.

Further study of the content, context, tone, and frequency of the self-talk of adults with Down syndrome may provide more insight into their private inner worlds. What we have observed and heard from family and caregivers suggests that self-talk is an important coping tool and only rarely should it be considered a symptom of severe mental illness or psychosis. A dramatic change in self-talk may indicate a mental health or situational problem. Despite the odd or disturbing nature of the self-talk, our experience at the Center indicates that self-talk allows adults with Down syndrome to problem-solve, to vent their feelings, to entertain themselves, and to process the events of their daily lives.